How to inspire children

One simple trick

Hello and welcome to this week’s instalment of How to be a Teacher. Here, I share tips I learn from my closest colleagues who, between them, have more than 70 years of experience in teaching.

I didn’t expect a simple game of bird cards to become the highlight of my Easter break – or to teach me something profound about excitement and learning. And I didn’t expect to see a link between that and something one of my amazing colleagues has been doing all year. But here’s what I learned from it…

It’s the Easter holidays here in the UK. Two weeks off to unwind from the job. Lovely jubbly. And the highlight of my time off so far has been a delightful day with my nephew.

My sister has raised a smashing kid. He’s a gentle soul, he followed my every move throughout the day and was quite polite for a little guy. He also didn’t make me get up and dance at the Bluey experience in town, like the other kids did with their adults, which I was relieved about. It seems dancing isn’t his thing either.

But what exactly was his thing?

If you’ve never had to entertain a child for a whole day – or you have children and you instinctively know how to keep them busy – you may not realise the pressure that comes with it. What will he like? What do I have to entertain him with? What do I need to buy in? What do I do? Seriously, what the hell do I do?

It turns out that – as someone who flits between a new hobby every two weeks – I happen to have a load of stuff lying around that was right up his strasse.

The electric drum kit went down a storm. He loved exploring the spotting scope. I have an untouched Lego set that he helped me with (we got as far as sorting the pieces into colours and then he switched off).

But he spent the most time playing with these:

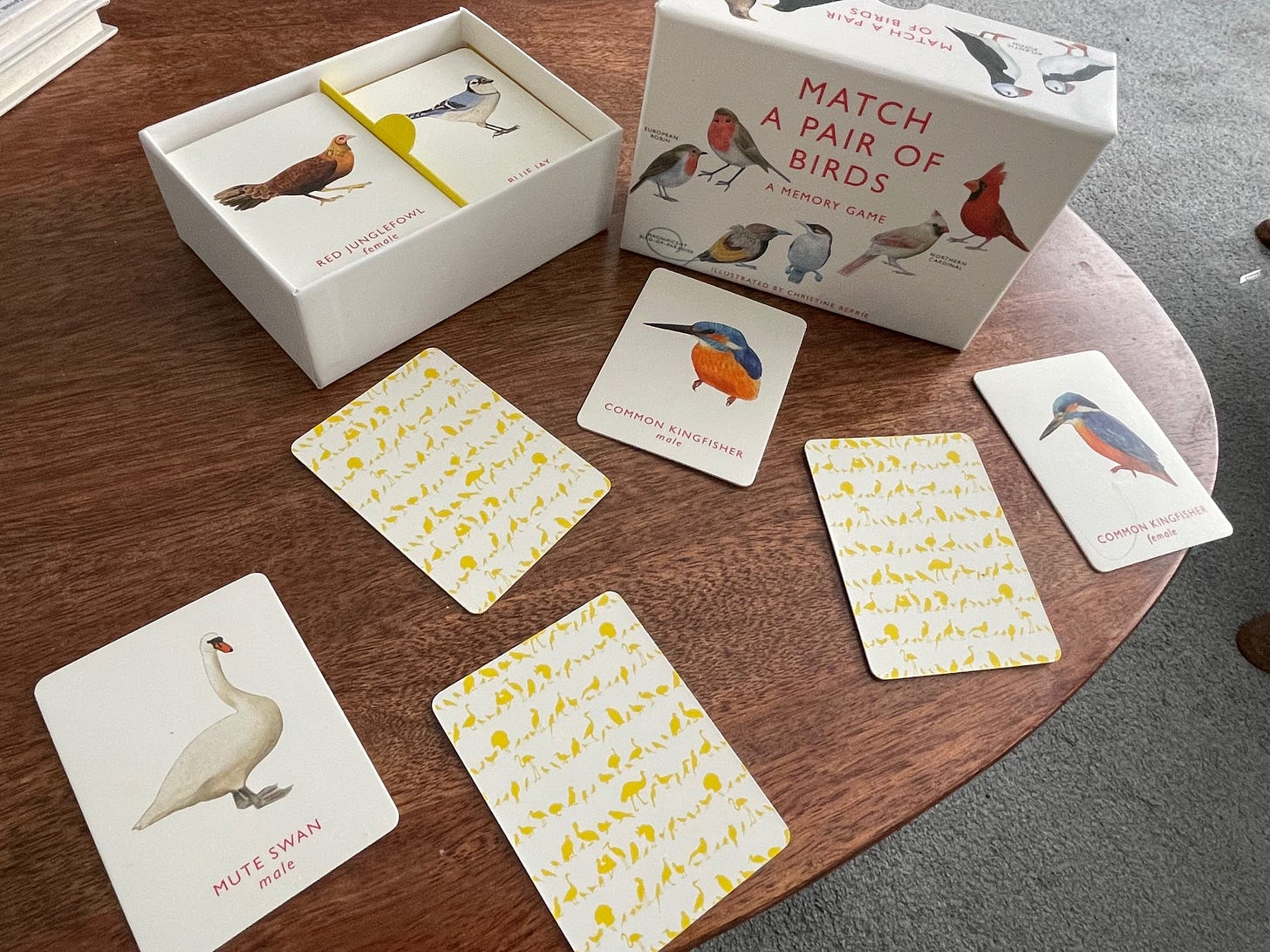

Bird pairing cards.

They’re simple flashcards, each with a photo of a male and female of the same bird species – robins, goldfinches, mallards – showing the subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) differences in plumage. His job was to match them.

He loved them. He played with them again and again. On our day out into town, we took them with us and had a mini play session on the train, and a few more while waiting for the day’s entertainment to begin at the local venue.

He didn’t just like flipping and matching them – he was exploring the differences between the males and females completely independently and was fascinated by how much they often varied.

(I’m going to explore this and the benefits of it in greater detail next week.)

Watching him so engaged made me wonder: what exactly hooked him in?

I think the first thing is that it was a game, and a very simple one. With short pieces of challenging text (the names of the birds), there’s a challenge that’s equal parts achievable, ambitious, and interesting.

But I also think my own natural excitement – and that of my partner, Aimeé – made a big difference. We’re big bird nerds (hence why we have a set of bird matching cards), and a game that revolves around them is something that genuinely excites us. We didn’t have to act excited.

And I think that translated to nephew. He felt the excitement and wanted a piece of it.

Before we knew it, he was naming birds by sight – no need to read the names – and spotting them on our walk to the train station.

Carnegie once wrote about the power of excitement in How to Win Friends and Influence People. In it, he tells the story of a man called Stan Novak. Stan’s son, Tim, was rioting about having to start kindergarten the next day. Rather than punish Tim for his aggressive and reluctant behaviour, Stan tried to get into his son’s mind.

He asked himself, “If I were Tim, why would I be excited about going to kindergarten?” The answer? Fingerpainting.

That night, he, his wife and his other son got to fingerpainting at the kitchen table, filling the room with a buzz of excitement. Before long, Tim wanted a piece of the action. The feeling of excitement translated from Stan to his son and hooked him in.

Psychologists call this emotional contagion – the idea that we subconsciously mimic the emotions of those around us. When a child sees genuine joy in an adult, especially around learning or play, it helps them feel safe, curious, and engaged. It’s not about pretending to care - it’s about letting them in on the things you already do.

Carnegie’s lesson has echoed in my own professional life, especially in the classroom – and it’s a beautiful story.

One of my colleagues (I’m going to call her Robin, after Robin Williams) always looks on the bright side of life. Robin has a student who most certainly does not. School, for them, is – for no apparent reason – a deeply unpleasant experience, one they seem to make harder for themselves at every turn.

But Robin has never given up on making school meaningful for the student.

She’s kept the focus on the positives. She’s supported the student through challenges. She’s set and maintained high expectations and fought tooth and nail for them to come away from primary school with a positive outlook.

Just before we broke up for Easter, another of my colleagues caught the student saying something in the corridor.

Something positive.

The student was beaming – a grin spreading from ear to ear – and bragging about all the positive points he’d earned on the school’s behaviour tracker that week.

They’ve taken something positive from school into the holidays with them. And I believe this is wholly down to the hard work of Robin and the fact that she has maintained a positive, excited attitude toward school. That little moment could signal the beginning of a transformation in the student - one unlocked by the sheer will and determined positivity of their teacher.

Her excitement for school may just have hooked him in.

From bird cards to behaviour trackers, it’s clear that genuine excitement has the power to draw others in. Whether you're a teacher, a parent, or an uncle, sometimes the best thing you can offer a young mind is your own passion – no acting required.

Want to read more?

Don’t just inspire the children around you to try something new or give something a go - help them achieve something great.

Thank you for reading. This is a free newsletter because I want it to be as widely-read as possible, especially by people finding their feet in the teaching world.

How can you help?

Share this with as many new, growing or aspiring educators as you can. The more the merrier. They’ll thank you for it - people usually do! Just click below and follow the prompts - it’ll only take a moment.

I also will be searching out this bird card game. And, I had a conversation similar to this with a colleague this week. She was feeling the need to bribe her students to engage in a school wide reflective and collaborative activity. And making a big deal about the bribing. I suggested that perhaps starting with the need for a bribe might be the opposite of where it was best to start. Interesting conversation is ongoing....

Loved your thoughts on how to inspire children. Yes, a delightful and positive experience. And, while sharing passion and positive outlook is definitely part of this success recipe, there’s another critical element to your interaction with your nephew: you allowed him to select what was of interest and to shift focus when interest waned, two key elements of early content and language learning. Since this is rarely an option in classrooms, we must do what we can to predict that interest. A key indicator is a student’s oral language decontextualized stage (OLDS), the degree to which the student continues to depend on the surrounding environment to send and understand messages. The work I cover in my Substack suggests students in grades K – 12 are developing through one of 5 stages. Here’s some information on the first 3 stages:

OLDS-1, [ages 1 -2, or English language Learners] total dependence on the environment. Communicate by pointing. Strong learning method is having someone describe (encode) objects and actions of learner interest.

OLDS-2 [ages 2 – 4, or some Title I students through grade 2]. Communicate in short phrases and by having a more advanced language user figure out what they are trying to say, then saying it. Strong learning method is sorting and matching while having access to one-to-one conversations.

OLDS-3 [ages 3 – 6, some Title I students through grade 8, many students on language IEPs through grade 12]. Communicate their own experiences in sentences connected by “And” or “And then.” Strong learning method is teacher presentation of repeated, visually supported sequences.

It sounds like your nephew was at OLDS-2 and on his way to OLDS-3. When teachers can recognize the OLDS of students they have a powerful framework to guide their lesson planning. Hoe you find this information of interest.