How to Save Yourself Hours of Marking - Part 1

Inspired by the most efficient educators of all - PE teachers.

Welcome to How to be a Teacher. I believe every teacher should have instant access to inspiration and experience. That’s why I share what I learn from my closest colleagues, whose 70+ years of experience I benefit from every day.

Below is my latest piece on how you can improve your marking and feedback system, one I use in every lesson and one that saves me hours of marking time each week.

You’ve got a handful of children in your class who aren’t making the progress you’d hoped for.

And, for good or ill, you’ve got targets to aim for - maybe a writing moderation goal, a times-table test at the end of the year or our old friend (sarcasm) SATs exams in Year 6.

So how do you help those who need your feedback, and can benefit from it, the most?

PE Teachers have the answer

When I left school, I took a gap year. No backpacking - I was bitting and bobbing on my grandad’s now animalless farm and taking up a professional football coaching qualification.

And this coaching training taught me something I still think about - and see, in school - today.

PE teachers have mastered live feedback; classroom teachers have not.

Yes, that’s right - this is something that sport coaches and PE teachers are brilliant at while classroom teachers are still years behind. It’s not often I hear it but they are the experts in live feedback and us classroom practitioners have so much still to learn from them.

Here’s a scenario from a PE teacher’s perspective:

You’ve taught the children how to perform the skill behind shooting for goal (kick with the top of the foot, head over the ball, keep it low)

You set up a game situation, like a 3 v 3, and let the players play (or apply the skill)

One player gets a chance to score, leans back too much and scoops the ball into row Z, showing room for improvement in the skill

What do you, the coach, do here?

Do you let them play on, making the same error four more times in the game without them realising then write them a note for next week’s training session that says ‘lean over the ball’ and expect them, of their own accord, to apply the skill perfectly from then on

Of course you don’t…

But, if you’re new to teaching, this is probably the only classroom marking system you’ve seen

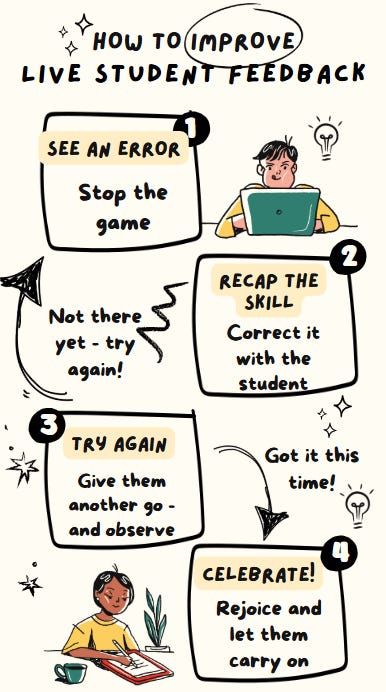

What the coach would do is:

Stop the game

Talk through the technique error with the student, showing them what to change

Replay the scenario so they have chance to apply what they’re learned and improve a small aspect of their performance

And it works so damn well.

In my early teaching years, this is what my colleagues have taught me to do in the classroom, too - stop a student where there is an error, show them how to correct it, give them another go on their one while you watch and point out why it’s better the second time.

This is what works best in the classroom… and we have mountains of research that tells us that retrospective, tick-box marking doesn’t work to back me up. It doesn’t improve academic attainment, it doesn’t improve skill levels, it doesn’t improve grades. It just plain doesn’t.

In last week’s post (click here to read it) I referenced Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam’s seminal research piece on feedback and assessment from way back in 1998. In it, they champion formative assessment (small, live moments of feedback throughout a student’s learning journey) because it supports the teaching of skills and knowledge. On the other hand, summative assessments (like end-of-year and end-of-unit tests) are ineffective in doing so and only reflect skill/knowledge being at a certain level.

But most schools in the UK still apply retrospective feedback

Even though it is the most colossal waste of time, the most unnecessary burden, on teachers in all settings, I’ll be my last quid that you’ll have met teachers who still taking heaps of books home to mark.

Over the next couple of weeks - inspired by the PE teaching model - I’m going to share methods my colleagues have taught me that will make your feedback more effective.

And I’ll even share one that even makes retrospective marking more meaningful.

Method #1 - Success criteria stickers

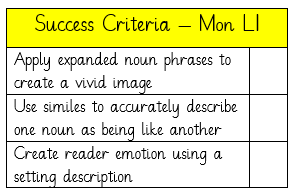

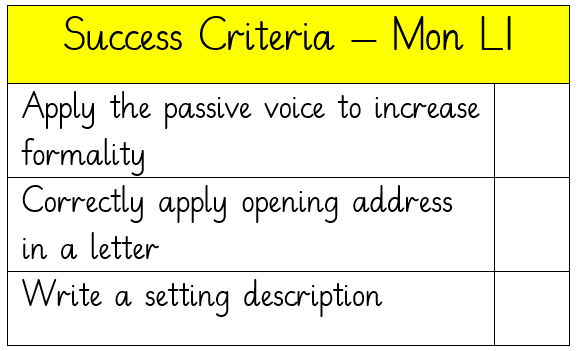

At the school I work in, we apply these in every lesson in every subject that uses a book. Here’s what they look like:

Each student sticks this in the top corner of the page in their books. Here’s how they work:

They make the learning goals clear

They help us keep the learning goals on skills and knowledge, rather than completing a task

The children can see during the lesson when they’ve been successful and - better still - you can show them during the lesson when they haven’t

How to get them wrong - and how to get them right

Too many goals = cognitive overload. Students won’t be able to apply skills well if you bombard them with targets and skills to apply. Plus, it will take up space in your book unnecessarily, so limit it to 2 or 3 criteria.

Focus on task over skill. The intention here is to improve a student’s skills and knowledge. We can all write a setting description; that doesn’t mean it’s any good.

Random, unconnected targets. There’s no point learning skills that aren’t going to pertain to the plenary task at the end of a lesson. The PE coach wouldn’t teach shooting in football then end a lesson by having the students put together a gymnastics routine. Keep it all linked.

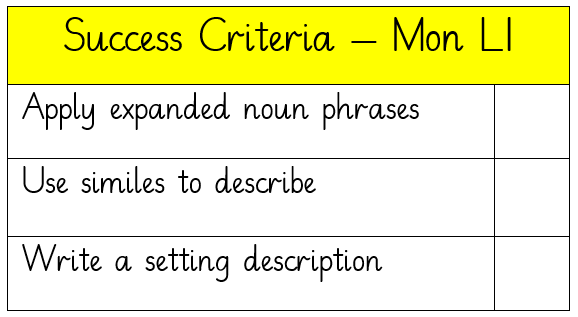

Here’s how it should look

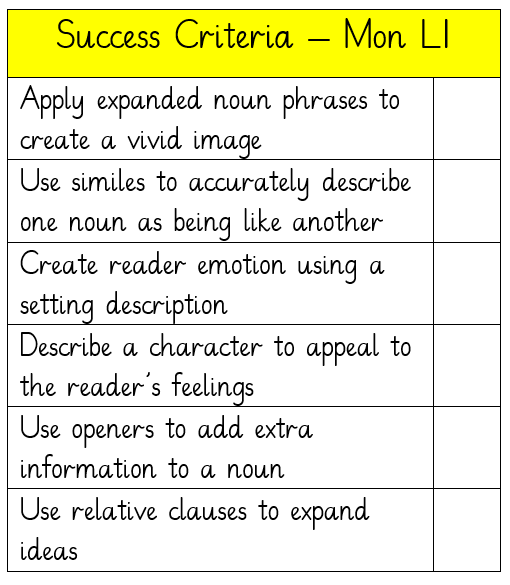

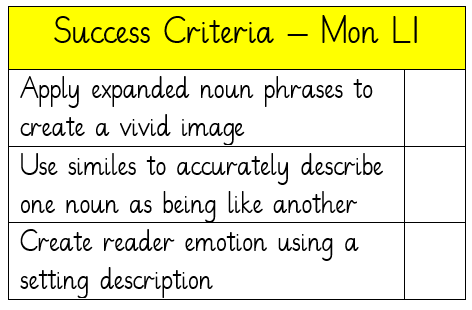

Below is a success criterium I have developed using the principles my colleagues have taught me. It also happens to be one that was plucked by our assistant headteacher as an exemplar and shown during staff training on the creation of success criteria.

Why does this success criteria sticker work better?

Appropriate number of targets. Keeping it to 2 or 3 goals prevents cognitive overload and increases focus where it should be. A football coach wouldn’t coach passing, tackling, crossing, shooting, saving shots and taking throw-ins explicitly in a single training session.

Focus on skills (creating a vivid image and invoking reader emotion) over task (using expanded noun phrases and writing a setting description). This makes the tasks meaningful and keeps the focus on the application, practice and improvement of the focus skills. The aim in a football training session wouldn’t be ‘score a goal’, it would be focussed on the technique that leads to goalscoring.

Skills are all linked. You will most likely use the lesson time (your input) to teach a skill that the children will practice at the end (their plenary). A football coach wouldn’t coach football skills then finish with a rugby, dance or gymnastics performance.

Keep it live

To make this truly effective, you need time to see some/most/all of your students’ work and establish whether they’ve met the criteria or not.

How?

Make sure there is ample time at the end of the lesson for them to work on the skills independently.

A 5-minute plenary will barely give you time to provide two or three students with feedback. In 20 minutes, though, I find I can get round quite a few of them. Do this every lesson and you have time to give every student feedback multiple times throughout the week.

Like what you’ve read?

Click the button below and choose another educator who you think should read this.

Black, P. and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/t4/learningandteaching/files/PGCTHE/BlackandWiliam1998.pdf

Want to see more?

Last week’s post talked about assessment and feedback as well. Here, I show you how to make summative assessments (like arithematic tests) worthwhile by working with a student as they fulfil it:

How To (Finally) Make Class Tests Worth Your Time

Quality is never an accident: it is always the result of intelligent effort - John Ruskin, celebrated writer, lecturer and philanthropist.

Below is another post about being the champion your students need. That could be with the academic support I described today; it could be something altogether more hollistic. A heart-warming tale (if I do say so myself) of how I made a difference to one student who needed it the most:

How to be the Champion Your Students Need

“Every child deserves a champion” – Rita Pierson, who needs no introduction.

PE teachers and music teachers too! Also in these scenarios, there is no end point. The top basketball player in the world practices these skills regularly, they do not learn how to shoot a free throw, make one, and then never practice again. There is always a way to get better. This is all the crux of my "every assessment is/should be formative" stance....what difference does it make what a student can know or do if we are not using that to help them move forward. Thanks for this actionable and common sense post.

As a PE teacher, I'd like to say thank you for the recognition of the craft ☺️